Back to blog

Brave, Firefox, Safari: Only Two Survived This Fingerprinting Test

Written by

Brightside Team

Published on

Dec 9, 2025

Brave browser is a very popular browser, because the developers went out of their way to protect the privacy of their users. This is really good. I a world where EVERYBODY WANTS TO FREAKING TRACK YOU, this goal alone should be applauded.

But... can it actually deliver (or to what extent)?

Let's do a test. We will need Brave, Safari, Firefox and a VPN.

Enable advanced tracking and fingerprinting protection in Safari, and set Enhanced Tracking Protection in Firefox to Strict (disable the "Fix major site issues" setting if present).

Now, go to coveryourtracks.eff.org and test each browser.

You'll likely see that Brave and Safari show randomized fingerprints, while Firefox gets identified as unique. (We'll come back to that later.)

Then go to fingerprint.com and see what you get. Scroll down and find the JSON export that fingerprint.com shows. Copy it and save it somewhere (not really needed, but does show some detailed information).

Next, close the websites, clear all cookies, all cache, all browser data. Close the browser and open it again. Enable a VPN and go to fingerprint.com again.

Do that 5-10 times, changing your IP with a VPN each time. Repeat the process over a week or a month. Go ahead, do it.

If you actually did this, let me guess - Brave was probably the only browser that was consistently re-identified or was re-identified more often than other browsers.

Finally, try creating a new Brave profile, and don't just change your IP—change the VPN provider altogether. Now you should be identified as a new user... hopefully. It doesn't actually work every time. It's basically a coin toss whether you'll be able to break re-identification by fingerprint.com. But even if on one of the attempts you are identified as a new user, there's a very high chance that this new profile will be identifiable going forward. And sometimes, even changing profiles doesn't help at all.

The most reliable way to break re-identification in Brave is by using Private Window with Tor. After testing this over several months, this was the only method that consistently broke re-identification in Brave.

Well, what about Firefox and Safari? Just clear browser data, relaunch the browser and change IP with a VPN (you don't even need to change the VPN provider). Hell, sometimes you don't even need to change the IP.

Jan 2026 correction: Further testing revealed that changing the OS-level timezone to match your VPN location helps break re-identification in Brave—not in every case, but consistently enough to be a practical mitigation strategy. However, Private Window with Tor remains the most effective anti-fingerprinting approach.

Notably, Safari with Advanced Tracking Protection enabled and Firefox with Enhanced Tracking Protection in Strict mode successfully break re-identification through clearing browsing data and changing VPN alone—no timezone adjustment required. Our theory is that Brave exposes sufficiently detailed GPU information that, when combined with an unchanging timezone across VPN changes, creates a distinctive pattern sophisticated fingerprinters can track. The unchanged timezone-VPN mismatch appears particularly identifying because it signals VPN usage while maintaining a stable tracking anchor. Additionally, Brave's farbling randomization may not be aggressive enough to obscure these hardware-specific identifiers, which we explore in greater detail below.

Why Do Safari and Firefox Succeed Where Brave Fails?

The key difference lies in how they combine generalization and randomization. Brave's "farbling" relies primarily on randomization alone - adding small random variations to your fingerprint, but still exposing precise hardware details like your exact GPU model (whatever chip you have - like "Apple M1 Pro", "NVIDIA RTX 3080", "Intel Iris Xe Graphics"), hardware-specific audio signature, exact CPU core count, etc.

Safari and Firefox take a fundamentally different approach: they generalize hardware information while also randomizing certain signals. Safari reports just "Apple GPU" instead of your specific chip model and randomizes canvas. Firefox reports something like "Apple M1, or similar" - grouping variants together instead of exposing precise models - while also standardizing certain values, giving all Firefox Strict mode users roughly the same audio output (~35.75), making you indistinguishable from millions of other Firefox users. Firefox then adds randomization on top: canvas fingerprints change with each session when you clear data and restart.

This compound approach - generalization + standardization + session-based randomization - puts you in a much larger anonymity set, making individual tracking much harder. When you clear data and restart, the randomized elements change, but you still blend into the same large anonymity set created by the generalized/standardized signals. This defeats fingerprint.com's ability to link you over time.

Brave's approach of randomization without generalization exposes enough stable, unique signals that advanced fingerprinting systems can create a persistent tracking anchor - even when you clear data and change IPs.

Author's note: Even when I disabled WebGL entirely in Brave - which should theoretically remove the main GPU fingerprinting vector - fingerprint.com STILL re-identified me with 96% confidence. The system detected privacy modifications (suspectScore: 19) but linked me to my previous profile anyway, proving that commercial fingerprinting uses multiple stable anchors beyond just WebGL. Fonts, math computation hashes, platform identifiers, and hardware specs all remained stable enough to create a persistent tracking anchor.

The funny thing is that tools like Cover Your Tracks often favor Brave's farbling approach because they report it as "randomized," while flagging Firefox as "unique" due to its standardized values.

But “Cover Your Tracks” Says I Have a Randomized Fingerprint

Well, Cover Your Tracks is not a commercial fingerprinter. In fact, fingerprint.com is the ONLY COMMERCIAL FINGERPRINTER THAT HAS AN OPEN DEMO.

That's very important to realize: NOBODY USES COVER YOUR TRACKS, AM I UNIQUE, BROWSER LEAKS AND SIMILAR TOOLS TO ACTUALLY IDENTIFY USERS IN THE REAL WORLD.

Banks don't use Cover Your Tracks. E-commerce sites don't use AmIUnique. Ad networks don't use BrowserLeaks. They use sophisticated commercial systems like fingerprint.com, ThreatMetrix, SEON, or their own in-house fingerprinting with server-side intelligence.

Educational tools like Cover Your Tracks are useful for understanding what data is exposed, but they don't test:

Stability of identifiers across sessions (the key to persistent tracking)

Server-side intelligence and fuzzy matching

Behavioral analysis

Real-world tracking persistence

So "unique" on Cover Your Tracks doesn't mean "tracked in real life", and "not unique" doesn't mean "safe from tracking." In worst case scenario it means totally nothing.

What Does Brave Say About This?

It's actually not a new thing at all - this was discovered some time ago. Here's what Brave's team says:

This approach creates an impressive-looking demo but is less effective for real-world scenarios where users visit sites over multiple days... We also suspect that the demo prioritizes generating 'consistent' fingerprints over accuracy. This means many users could be assigned the same fingerprint, leading to a high false-positive rate.

But here's the problem: Safari gets nearly identical results on Cover Your Tracks as Brave, and Safari successfully breaks re-identification by fingerprint.com.

The thing is, most commercial fingerprinters are not available for testing. They all require enterprise contracts. They're definitely not available to developers who are trying to build tools to defeat them.

So, should the results of the fingerprint.com demo be discarded? Well, it is still the only demo of an actual commercial fingerprinter that's openly available. We can't validate against other commercial systems, but it's our only window into how real-world commercial tracking actually works.

What Does Research Say?

There's this research paper published in 2025 titled "Breaking the Shield: Analyzing and Attacking Canvas Fingerprinting Defenses in the Wild." It specifically tests Brave's farbling and other randomization-based defenses, and demonstrates that with statistical analysis, adding random noise to fingerprints can be defeated - and it's barely an inconvenience. The researchers successfully attacked "nine extensions and the Brave browser's 'Farbling' mechanism."

Their conclusion: "unfortunately, no fully deployable defense against canvas fingerprinting attacks exists currently" - but they found that randomization-based techniques (like Brave's farbling) are particularly vulnerable, while fixed/standardized outputs (closer to what Firefox does) are more robust.

This research on mobile browsers found that Safari has the best privacy protection amongst mobile browsers. The desktop version appears to be just as good.

What About Cross-Site Tracking?

Even if we narrow the discussion to cross-site tracking prevention specifically, it's really hard to judge how effective Brave actually is.

Cross-site trackers use the same fingerprinting APIs as first-party tracking - the same canvas calls, the same WebGL queries, the same audio fingerprinting techniques.

If Brave can't prevent first-party tracking by fingerprint.com despite users clearing data and changing IPs, and these cross-site trackers use these exact same fingerprinting APIs, Brave's protection is likely insufficient for cross-site tracking as well. The research showing that randomization can be defeated through statistical analysis supports this.

An important caveat: this limitation isn't unique to Brave. Since commercial ad networks have even more sophisticated infrastructure and larger databases than fingerprint.com, any browser or tool that performs well on fingerprint.com's demo might still struggle against other major tracking networks. Safari may perform better than Brave on fingerprint.com's demo, but this could give a false sense of security - we're still limited to testing against just one commercial fingerprinting system, and we have no idea how these protections hold up against the full ecosystem of commercial trackers with potentially different techniques and capabilities.

What About Firefox's Resist Fingerprinting?

There isn't much to say, because it works even better (and aggressively) than ETH Strict mode, though it may break some websites that legitimately need certain APIs.

Implementation in Mullvad Browser (a privacy-focused Firefox fork) is really good and well-configured. Actually, vanilla Firefox can be set up to be 99% just as hardened as Mullvad, but it requires more manual configuration than just downloading Mullvad.

So Is Brave a Bad Choice?

Heeeell no. It's still a MUCH BETTER CHOICE than other non-privacy focused browsers like Chrome, Edge, or standard Safari configurations.

Brave still blocks ads, blocks many trackers, has built-in HTTPS upgrading, and provides significantly more privacy than mainstream options. For general browsing, when you log in to your social media accounts and use websites normally, it's still really good.

It just has limitations for specific threat models. If your goal is to evade sophisticated commercial fingerprinting and remain unlinkable across sessions despite clearing data and changing IPs, Brave's farbling appears insufficient based on testing.

For macOS users specifically, Safari with Advanced Tracking and Fingerprinting Protection enabled appears just as effective if not slightly better (strictly in terms of fingerprinting protection).

For maximum fingerprinting resistance while maintaining reasonable usability, Firefox with Enhanced Tracking Protection set to Strict (or Mullvad Browser) appears to be the most effective option currently available.

The Big Challenge

The elephant in the room is that fingerprint.com is the ONLY commercial fingerprinting service that has a publicly available demo. While this makes it invaluable for privacy testing, we can't validate these results across other commercial systems like ThreatMetrix, Iovation, or SEON (which all require enterprise contracts and don't offer public testing).

It's entirely possible that different commercial fingerprinters use different techniques or weights, and browsers might perform differently against each. But without public access to test against these systems, fingerprint.com's demo remains our best - and only - window into real-world commercial fingerprinting effectiveness.

So it's really hard to say with absolute certainty how effective any of this is across the entire tracking ecosystem. But based on months of testing against the one commercial fingerprinter we CAN test, combined with academic research validating that randomization-based defenses can be defeated, the pattern is clear enough.

Testing methodology note: These conclusions are based on several months of consistent testing using the protocol described above - clearing all browser data, restarting browsers, changing IP addresses via VPN, and testing across multiple browser profiles and VPN providers. Results may vary based on hardware, operating system, and specific configurations.

P.S. Proton (the company behind ProtonVPN and ProtonMail) also did their own browser comparison and fingerprinting test, and it’s worth addressing how their conclusions differ from what you see in this article.

They tested browsers using Cover Your Tracks (EFF’s tool) on “fresh installs” and concluded that Brave was the only browser that was completely effective against browser fingerprinting on desktop and Android, while Firefox’s experimental protections “didn’t prevent unique identification.” The key detail is that their test only checked whether the fingerprint looked “randomized” or “unique” in a single session on Cover Your Tracks, which does not simulate how commercial fingerprinting actually works.

The testing in this article uses fingerprint.com, which is an actual commercial fingerprinting service with server-side intelligence and persistence. Here, Brave consistently gets re-identified across sessions and IP changes, even after clearing all browser data, while Firefox (Strict / RFP) and Safari can reliably break re-identification under the same conditions. This matches academic research showing that randomization-based defenses (like Brave’s farbling) can be defeated, and that single-snapshot tools like Cover Your Tracks do not reflect real-world tracking persistence.

Start your free risk assessment

Our OSINT engine will reveal what adversaries can discover and leverage for phishing attacks.

The Bigger Picture: Security Awareness Training Starts with Digital Exposure

This analysis shows how much data your browser leaks through fingerprinting. But browser tracking is only a small part of your total digital exposure. Most security incidents don't require sophisticated fingerprinting when attackers can simply search for publicly available information.

Work emails displayed on LinkedIn profiles, compromised passwords circulating on the dark web, phone numbers sold by data brokers, and location data from social media posts create a rich intelligence source for spear phishing attacks. With 95% of data breaches caused by human error and 66% involving phishing, the human element is the critical vulnerability.

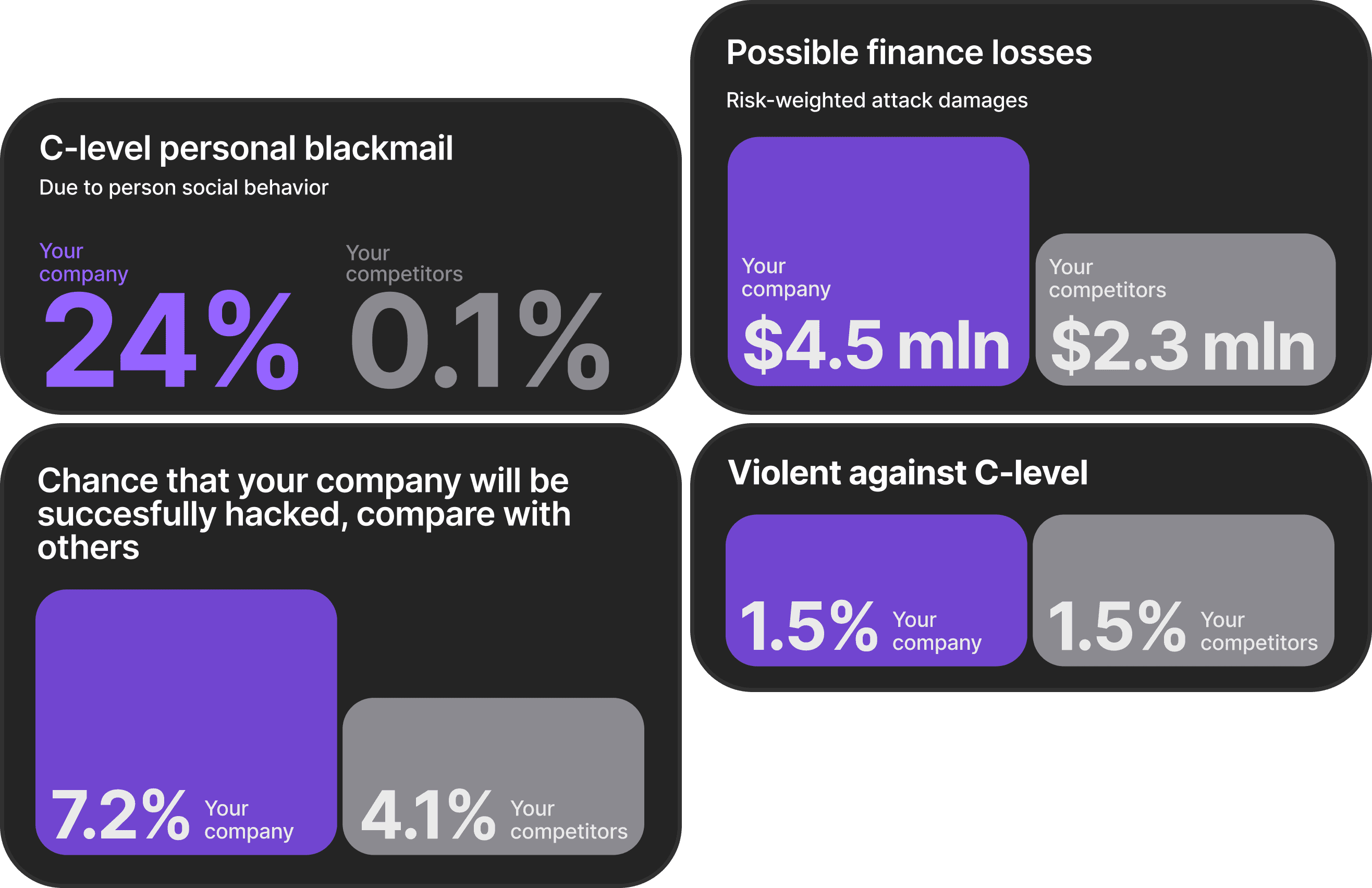

Brightside takes a comprehensive approach to this problem. The platform uses OSINT technology to scan users' complete digital presence, identifying vulnerable data across six categories. When exposure is found (like a work email publicly visible on LinkedIn), Brighty guides users through step-by-step remediation, explaining why it matters and how to prevent future exposure.

For security teams, this creates quantifiable risk metrics. The Admin Portal provides individual vulnerability scores for each employee and organizational security posture metrics, while the Employee Portal empowers workers with direct privacy control. This reduces corporate vulnerability while respecting personal boundaries (administrators see aggregate metrics, not personal details)